The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has set ambitious CO2 reduction targets for the marine sector, but the regulator relies upon member states and ship operators to take decisive action to achieve the goals.

The maritime CO2 footprint

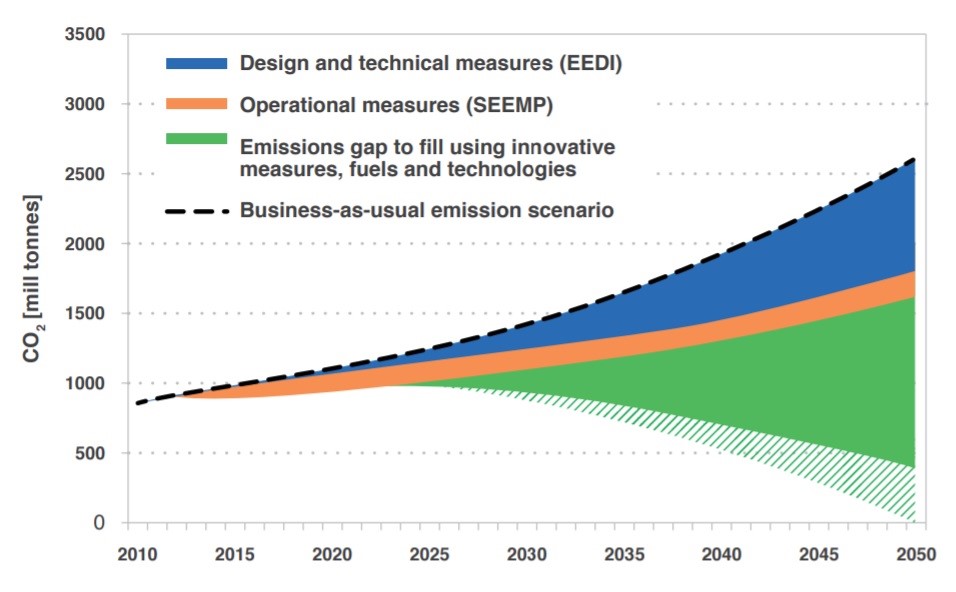

International trade and the global economy are heavily reliant on maritime trade: around 80% of global trade by volume is carried out by sea. Shipping CO2 emissions grew 9.3% to 1,056 million tonnes in 2018 (opens a new window) compared to 2012. The share of shipping emissions in global anthropogenic emissions has increased from 2.76% to 2.89% during this period. The IMO forecasts show that this share will grow by between 50 and 250% by 2050 if the growth of maritime activity continues at its current rate.

The IMO goals

The IMO aims to reduce the average CO2 emissions per transport work (carbon intensity) across international shipping by at least 40% by 2030 (opens a new window), pursuing efforts towards 70% by 2050, compared to 2008. Further, the organisation intends to reduce the total annual greenhouse gas emissions (CO2, methane, nitrous oxide, water vapour, fluorinated gases) from international shipping by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels.

A flurry of solutions

The IMO has adopted an Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) with measures that are legally binding to all member states. The regulator has also established a series of baselines for the amount of fuel each type of ship burns for a certain cargo capacity. The IMO will make the baseline targets tougher for new ships in future. By 2025, all new ships will need to be 30% more energy efficient than those built in 2014.

The IMO has also introduced Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) regulation requiring existing ships to have an energy efficiency management plan in place that includes looking at improved voyage planning, cleaning the underwater parts of the ship and the propeller more often, introducing technical measures such as waste heat recovery systems, or fitting a new propeller.

IMO research also suggests that there is significant untapped potential to reduce shipping emissions cost-effectively, referring to a variety of technical and operational measures such as slow steaming, weather routing, contra-rotating propellers and propulsion efficiency devices. These and other measures can deliver more fuel savings than the investment required, according to the IMO.

Ship operators are also looking into alternative fuels, including liquid natural gas, biofuels and blended fuels. Retrofitting engines to make them compatible with the new fuels can be a costly process and significant investment is going into the development of low carbon and zero-carbon dioxide fuels.

Source: IMO

Industry impact on innovation and investment

If the proposed carbon regulation is implemented, it will entail complex compliance challenges: 174 countries need to ratify the IMO regulation into national legislation and ports need to offer the required decarbonisation options.

Unprecedented investment and international cooperation will be needed if the industry is to meet the IMO's targets on carbon emissions. Future IMO regulations are set to create compliance obligations for ship owners and operators. Depending on the timeline and ambition of future IMO regulation on greenhouse gas emissions, this could lead to early scrappage and expensive retrofits affecting profitability in the industry. The rise of environmental regulation has highlighted the need for operators to maximise efficiency to maintain competitiveness.

The measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are expected to have a disproportionate effect on smaller nations, particularly island nations that rely heavily on maritime trade. Similarly, larger operators may be in a better position to cope with the new technology costs. Maersk, for example, aims to complete its first carbon-neutral voyage (opens a new window) (using carbon-neutral methanol) by 2023 and has committed to equip all new build vessels with dual-fuel technology, enabling either carbon-neutral operations or operations on standard very low sulphur fuel oil.

The technology options that the maritime industry is currently exploring are relatively novel and have never been produced or deployed in any great scale. A study by the Lloyd’s Register (opens a new window) identifies biofuels as the most profitable zero-emissions solution, noting that they consistently outperform their zero emission competitors (electric, hybrid hydrogen, hydrogen fuel cell, hydrogen +ICE, ammonia fuel cell, ammonia +ICE) economically due to their low capital cost implications for machinery and storage, and low fuel and voyage costs. The second most economically effective option is ammonia and hydrogen with internal combustion machinery, a solution that has a lower capital cost for propulsion machinery than the fuel cell and electric motor combination, according to the report.

Industry impact – insurance

Regardless of which of the solutions will be successful, it appears that investment in specialist technology both ship-side and shore-side is inevitable and is likely to impact the value of those ships. Further, there may be operating complications or specialist parts or repairs required. If these risks come to fruition, it could eventually reach the sphere of insurance.

Calculating the exposure and cost of that risk will be the challenge of hull & machinery underwriters in order to determine the premium attached thereto. In an already-hardening market, additional costs reflected by these further changes are unlikely to be welcome.

Any increase in quantity and severity of regulation also raises a ship operator’s potential exposure to liabilities. Whilst protection & indemnity cover related to fines imposed pursuant to a breach of the IMO’s regulations is typically discretionary, it will certainly be an exposure that cannot be overlooked by both the ship operators themselves and their insurers.

Emerging risks

The implementation of greenhouse gas regulations also involves some climate-related litigation risk.

Corporate climate commitments could prompt future climate-related disclosure litigation, according to a Lloyd’s emerging risks report (opens a new window). If companies publicly commit to certain targets even though non-binding, this can result in future shareholder legal action against them if they fail to meet them.

Further, if companies fail to disclose key business risks from alternative fuels and emissions reductions or to set clear targets, this could also lead to disclosure litigation over withholding information vital to the business.

New technologies are also likely to carry significant intellectual property risk for maritime companies, as ship owners and charterers try to gain a competitive advantage by performing in-house research and by implementing such technologies early, the Lloyd’s report suggests. These businesses are likely to become increasingly concerned about securing this advantage through intellectual property rights.

Insurable values of vessels are set to rise from implementation of retrofits and the fitting of costly new technologies, possibly increasing hull insurance premiums. At the same time, uncertainty associated with the deployment of different technologies and upstream emissions could make risks difficult to price for insurers.For further information, please contact:

Stephen Hawke, Managing Director, P.L. Ferrari

T: +44 (0) 207 933 2512

E: stephen.hawke@plferrari.com (opens a new window)

Alexander Gray, Head of Marine P&I Lockton Singapore

T: +65 6221 1288