Scientists expect that extreme weather events like the devastating floods that recently struck Germany will become more frequent. This will require a new plan to save lives and reduce the losses for the population and the economy.

In mid-July, burst rivers and flash floods caused at least 177 fatalities (opens a new window) in Germany. Parts of Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia were inundated with 148 litres of rain per sq metre within 48 hours (opens a new window) in a part of Germany that usually sees about 80 litres in the whole of July. The water masses made houses collapse, ripped up roads and power lines, and cut off entire communities from power and communications. Floodwaters produced widespread damage to homes and swept away vehicles, bridges and other infrastructure. It is dubbed the worst natural disaster in the country in more than half a century (opens a new window).

Rising likelihood of extreme weather events

While there may be no proof that links the event directly to climate

change, scientific models predict that such extreme flood events are

likely to happen more frequently in the future as average temperatures

rise on Earth.

Since the pre-industrial period, human activities are estimated to

have increased the earth’s global average temperature by about 1 degree

Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit), a number that is currently increasing

by 0.2 degrees Celsius (0.36 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade, according to data by NASA (opens a new window).

A warming of the atmosphere and oceans makes severe rain more likely because higher temperatures let air hold more water vapour (opens a new window): for every degree Celsius of warming, the atmosphere can absorb 7% more moisture. Wetter air leads to stronger bursts of rainfall.

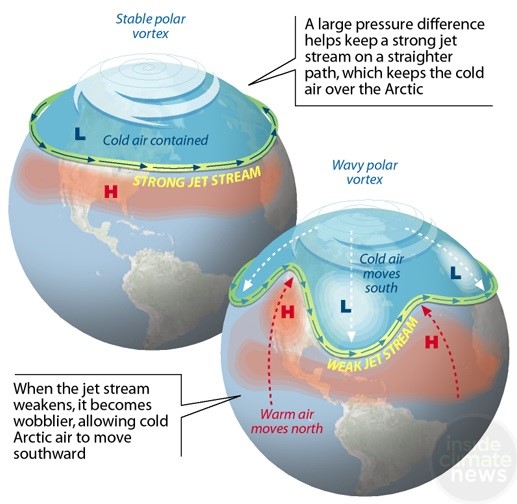

Further, arctic temperatures are rising twice as fast as the global average, and research shows (opens a new window) that a shrinking temperature difference between the equator and the poles weakens the jet stream. Racing from west to east, the northern jet stream transports moisture and moves masses of cold and warm air and storm systems along its path, driven partly by the temperature contrast between masses of icy air over the North Pole and warmer air near the equator. The weakening of the jet stream is making it wobblier (opens a new window), pinning large high and low pressure systems in place above North America, Europe, and Asia. Under the highs, temperatures often soar, while persistent rains fall where the lows are entrenched.

Source: Inside Climate News

More instances of weakened atmospheric circulation and subsequently

stalled weather patterns do increase the probability of extreme rainfall events that can subsequently result in major flooding.

Writing in the journal Nature, a team of US-based researchers found (opens a new window)

that up to 86 million people, driven by economic necessity, moved into

known flood regions between 2000-2015, and that the number of people

exposed to floods worldwide has surged almost a quarter over the last

two decades. The researchers examined satellite data from twice-daily

imaging of more than 900 individual flood events in 169 countries since

2000. Computer modelling produced estimates that climate change and

shifting demographics would mean an additional 25 countries facing a

high risk of flooding by 2030.

Saving lives

The new threat levels for the population may require a review of the

catastrophe communications process in place. A warning system in

Germany, which includes a network of sensors that measures river levels

in real time, functioned as expected, but the waters rose so swiftly, to

heights beyond previously recorded levels, that many communities’ response plans were ineffective.

There was a “mass communication breakdown” between officials, media and the public in many affected areas, according to Hannah Cloke (opens a new window), a hydrologist at the University of Reading. The population was not

aware that such extreme floods were a real threat to their lives. Consequently, the unprecedented amount of rain falling in a short period

of time caught the population off-guard. Citizens took too few precautions and local authorities were ill-prepared. Experts therefore partially blame poor communication about the high risk posed by the flooding for the significant loss of life.

A costly event

More than 43,400 buildings are estimated (opens a new window) to have been impacted by the first wave of floods in July in Europe, which affected mostly Germany but also parts of Belgium, Luxembourg and The Netherlands.

Germany’s insurance association (GDV) estimated the losses from flooding (opens a new window) in the German regions of North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate to cost insurers between €4bn and €5bn. Further,

businesses are likely to submit claims to insurers for property losses

and business interruption.

Fitch Ratings expects the floods in Germany to add up to 5pp to German non-life insurers’ net combined ratios, a profitability measure. A ratio above 100 percent means that the company is paying out more money in claims that it is receiving from premiums. A rise in an insurer’s combined ratio is likely to result in higher premium for insurance buyers.

The flood costs are also set to affect reinsurers. The destruction caused to Germany and parts of Belgium is estimated to result in reinsurance losses of between USD2-3 billion, according to Berenberg analysts (opens a new window). The costs could be much higher, with reinsurers surveyed by Insurance Insider estimating the loss (opens a new window) at around EUR5 billion. The costs of reinsurance in Asia and the US went up over the past couple of years as hurricanes and wildfires caused higher losses. Insurers usually pass these higher costs on to their clients.

But the total economic cost of the events will be much higher. In Germany, flood protection is not included as standard in homeowners’

policies but is available as an extension to the cover. Data by the German Insurance Association (GDV) shows that 54% of properties in Germany lack any insurance coverage against weather phenomena. In the affected region, this share is expected to be even higher. The German government is releasing additional funding to pay for the reconstruction.

"In addition to the sudden and tragic loss of life and destruction of

buildings and infrastructure, floods can create an impact on the wider

environment with long term pollution issues. This can include silt

movement, tank losses, pipeline ruptures, lead and mercury contamination of grazing land or water supply to name a few." James Alexander, Lockton Environmental Practice Leader

Reassessing the risk

Insurers and reinsurers traditionally focused on predicting big weather events that can cause widespread damage, but due to climate change and urban sprawl, they are now increasingly incorporating (opens a new window) secondary-peril models.

The prospect of increased frequency of extreme weather events has

insurers rapidly updating their risk-assessment models and recalculating the price of insurance. Property insurers faced an estimated $18 billion bill for damage to homes and businesses from the long stretch of frigid weather in Texas and numerous other states, the equivalent of a major hurricane, The Wall Street Journal reported (opens a new window) earlier this year.

Insurers may, in some cases, also drop coverage altogether due to the increased frequency of extreme weather events. In California, for example, some insurers chose to not renew insurance policies for homeowners in high-risk areas for wildfires after wildfires killed dozens of people and racked up more than $24 billion in insured losses in two years.

"As climate change is leading to more frequent severe weather events

such as flooding, insurers continue to invest in enhanced flood mapping

tools to minimise their exposure and persist to look more closely at

their pricing and flood deductibles at an individual policy level to

cover claims, expenses, reinsurance and provisions for large

losses." Gregg Cordell, Senior Vice President, Lockton Global Real

Estate Practice

Protecting buildings and infrastructure

The destruction caused by extreme rainfall partially depends on soil

saturation, topography and urban development, which can prevent water

from draining away.

A new generation of climate models is capable of providing more

precise projections for changes in high-impact weather extremes such as

short-duration heavy precipitation.

Understanding the risk for real estate and infrastructure means looking 20 to 30 years ahead (opens a new window) through weather modelling to quantify the likelihood of an event and the likely effect on a property.

While quantifying the potential damage requires significant computing power and plenty of data, for example from governmental agencies, Artificial Intelligence (AI) can help refine and facilitate the process. Furthermore, the Internet of Things (IoT) is an important piece of

technology to measure the effect of weather events and deliver the trigger basis for parametric insurance claims.

Parametric flood insurance policies use a sensor attached outside the

building to collect flood data. When the pre-agreed flood depth is

reached, the full insured amount is automatically paid out and the

insured can determine themselves how to best spend it. Businesses can

select the trigger depth and payout amounts when purchasing the product, giving them a lot of flexibility in how to design their protection.

Lockton has partnered with FloodFlash (opens a new window), a registered coverholder at Lloyd’s of London which offers a simple and flexible parametric flood insurance policy.

Governments, companies, investors, and individual property owners

should assess available data to improve protection strategies for their

assets. This can, for example, lead to risk mitigation through the use

of more suitable building materials, new types of architecture design,

or by building protections; for example in form of flood barriers. Further, intelligence can lead to (re-) building in areas where the risk is lower. This can help reduce claims and contribute to lower interruption and more resilience.